Henry Blodget, CEO of business news site Business Insider, recently published a blog titled Time for a Better Capitalism. The article examines how U.S. corporations think of American employees as “costs,” instead of as consumers. Blodget claims that shift has, over time, fundamentally changed American capitalism.

By paying good wages, investing in future products, and generating reasonable (not “maximized”) profits, American companies in the 1950s and 1960s created value for all of their constituencies, not just one. As a result, the country and economy boomed. Over more recent decades, however, this balance has radically shifted.

The richest 1% of Americans now own nearly 45% of all the country’s wealth, near the highest level since the “Gilded Age” of the 1920s. Millions of Americans who work full time for highly profitable corporations earn so little that they’re below the poverty line. The bottom 50% of Americans own nothing.

Talk to people in the money management business, and they’ll proclaim this as a law of capitalism. They’ll also cite others, including the idea that employees are “costs” and competent managers should minimize these costs by paying employees as little as possible. The problem is that when capitalism is practiced the way it is today, wealth becomes so concentrated that much of it doesn’t get spent.

— Henry Blodget, Time for a Better Capitalism

American Employees and Shrinking Wage Share

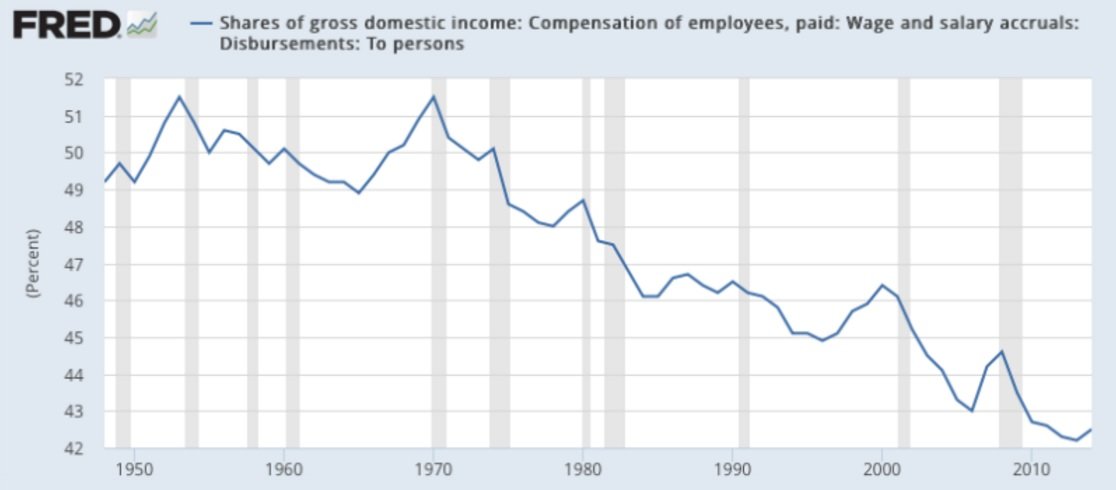

Do corporations now exclusively view their employees as just “costs?” Take a look at one of Blodget’s charts, which shows the last six decades of American wages as a percentage of the economy:

Does this look right to you? The United States has economy driven by consumer spending. If the middle class has less to spend on consumer goods, doesn’t that make everyone worse off? Should we be thinking of employees as “costs” or as “consumers?”

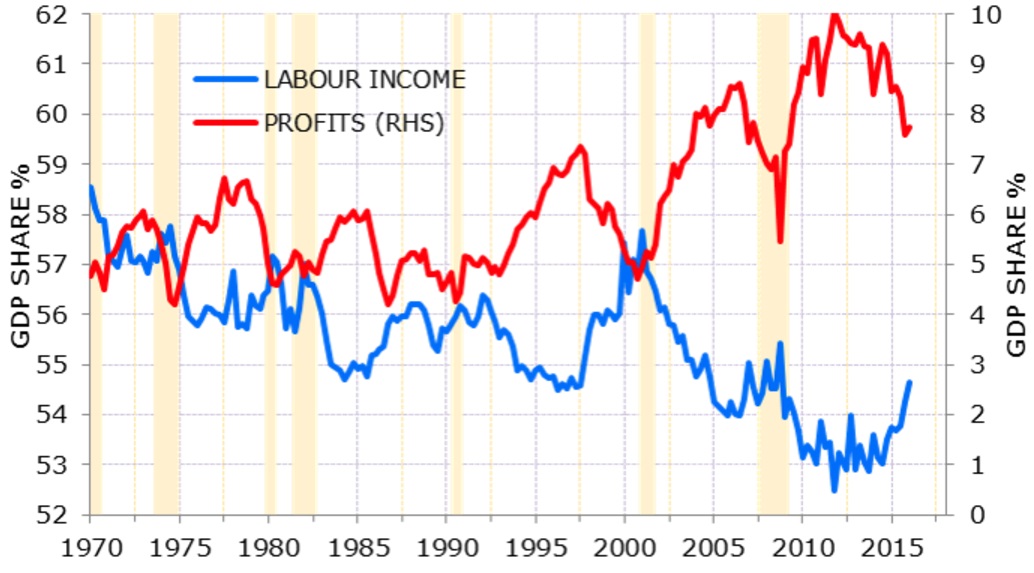

Now look at Cuffelinks’ comparison of wages and profits since 1970. This chart shows a clear divergence in the share of growth going to employee labor costs versus corporate capital by way of profit:

Trade policy, automation, globalization and immigration have all contributed to driving down the wages of the least-skilled American employees. Yet none of these has driven down wages as much as minimization of labor costs by American corporations. “Some level of ability to move up the economic ladder is important to democratic stability,” said Tiziana Dearing, professor of practice at the Boston College School of Social Work. “When people lose their faith… it’s usually politically destabilizing. If we have no middle class left, we’ll have no consumer class left.” No one to buy goods and services.

Trade policy, automation, globalization and immigration have all contributed to driving down the wages of the least-skilled American employees. Yet none of these has driven down wages as much as minimization of labor costs by American corporations. “Some level of ability to move up the economic ladder is important to democratic stability,” said Tiziana Dearing, professor of practice at the Boston College School of Social Work. “When people lose their faith… it’s usually politically destabilizing. If we have no middle class left, we’ll have no consumer class left.” No one to buy goods and services.

The “Financialization” of Corporate America

Rana Foroohar addresses these issues in his recent book, Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business. The author argues American employees’ economic ills have at their root “financialization,” or the increasing political power of financiers and the CEOs they enrich and the “markets know best” ideology that have driven wages down over the past few decades. Despite currently taking around 25% of all corporate profits, the financial sector creates a mere 4% of all American jobs. Foroohar recommends, among other policy solutions, rethinking who companies are run for. He believes that companies should be run not only for shareholders but also for workers. This would require a retooling of capital markets to encourage corporate long-term growth, not just short-term stock value alchemy.

The U.S. is the wealthiest country in the world. Yet income inequality is greater here than in any other democracy in the developed world. Should the American economy be a zero-sum game between financial wealth-holders and the rest of America?