We should break up the banks. Only the full separation of depository banking and investment banking can protect consumer savings from banks’ naked speculation. Our nation needs a modern-day Glass-Steagall Act, the Depression-era banking system repealed in 1999. Commercial banks should not be allowed to make investment decisions with customers’ depository funds.

When Wells Fargo Bank loses its Better Business bureau accreditation for opening millions of unauthorized accounts, that’s one thing. But when taxpayers have to bail out an entire financial sector, it’s time to re-think our approach to “too big to fail.” Since the repeal of Glass-Steagall, U.S. banks have grown larger and more complex: “Banks such as JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America now have trillions in assets with highly intertwined commercial and investment banking operations.”

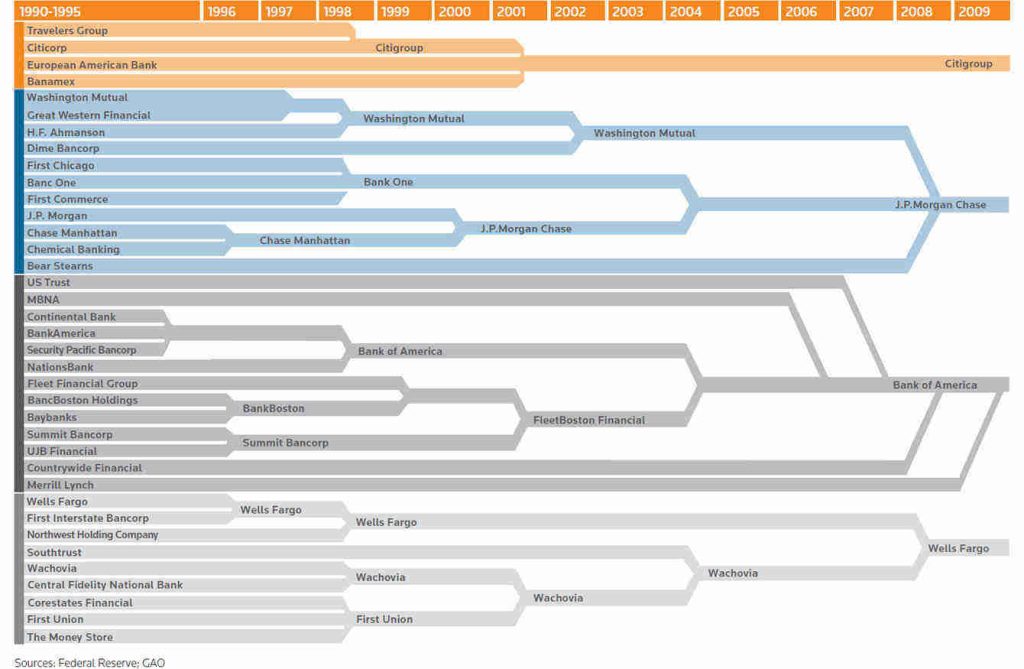

Just take a look at the consolidation that took place in American banking over just 13 years:

As a result, the big banks have grown more powerful than ever.

Growth and expansion were propelled in part by the relaxation of trade barriers and deregulation of markets – a process that started as far back as the ’70s and continued until the Great Recession that began in 2008.

Whereas the top five banks accounted for 37% of global fixed income market share in 2005 – just before the crash – today they make up 48%. Though reordered somewhat, the top five institutions in 2005 – Deutsche Bank, J.P.Morgan, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Barclays – still occupy those positions today.

“Only the Strong Survive,”

John Colon, Greenwich Associates (via Reuters)

Break up deposits from investments

No one seriously suggests abolishing investment banking. Instead, banks should use investment funds only for investing, and depository funds only for interest. The concept is simple and intuitive and commonsense and absolutely infuriates the banking industry.

The truth is that the big banks love being able to invest the combined power of all bank funds regardless of source. The rewards for a successful investment are not passed on to depositors, however, only the risk.

I don’t suggest this lightly. Any changes to Dodd-Frank regulations would have a big impact on wealth management for banks and customers alike. In the short-term, consumers may have fewer available financial products and receive lower interest rates on savings. Yields on managed wealth, too, may be temporarily suppressed. But we should want to prevent otherwise inevitable misinvestment leading to another financial system meltdown. To do that, we must establish a bright line between the funds the banks may and may not invest.

Living wills are not enough, and the next financial crisis may not be one so easily fixed as the last one. Only ex ante segregation of investable from non-investable funds will prevent the certain misinvestment of depository funds.

A modern-day Glass-Steagall

Treasury Secretary Stephen Mnuchin and lightning rod Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) went at it in a recent Senate hearing. Mnuchin made clear that Glass-Steagall has no place in President Trump’s financial agenda: “There are aspects of [Glass-Steagall] that we think may make sense, but we never said before that we supported a full separation of banking and investment banking.”

Mnuchin’s reason? “If we did go back to a full separation, you would have an enormous impact on liquidity and lending to small and medium-sized businesses.” That position is indefensible.

Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999. Mnuchin’s “concern” begs the question as to how small businesses possibly existed prior to 1999. The answer is quite simple, actually: worthy business plans can find lending in nearly any financial environment. Moreover, small business lending is inherently risky and should come from investment funds, not depository funds. Mnuchin’s reason for opposing Glass-Steagall is supported by neither history or logic.

A modern-day Glass-Steagall rule separating investment and depository funds would protect against investment risks like those that lead to the Great Recession and shore up our nation’s financial stability over the long-term, despite the possible adverse immediate effects on consumers and small business.