Just released is an insightful new white paper from the Brookings Institution’s William A. Galston entitled The New Challenge to Market Democracies. The author goes further than simply asserting that better policy can reverse the now decades-old trend of income inequality. Instead, he suggests that the feasibility of liberal democracy can be cast into doubt. One thing is clear from the article: the Great Recession still troubles the middle class in America. Galston writes:

In the five years since the official end of the Great Recession, wages have only kept up with inflation, while family and household incomes have barely budged off their recessionary lows and remain far below their pre-recession peak. The share of national income going to wages and salaries is at its lowest point in nearly half a century, and businesses have found ways of raising production without hiring more workers, at least in the United States.

The majority of workers who have found new jobs are earning less than they did prior to the recession, and the number of people working part-time who want full-time jobs remains very high. Relatively few jobs now being created offer incomes in the middle range: most are in lower-wage services, and most of the rest are in the high-skilled professions that require advanced training. These trends bode ill for the future of the middle class; many parents now doubt that their children will enjoy the same opportunities that they did.

Creating a sustainable middle class

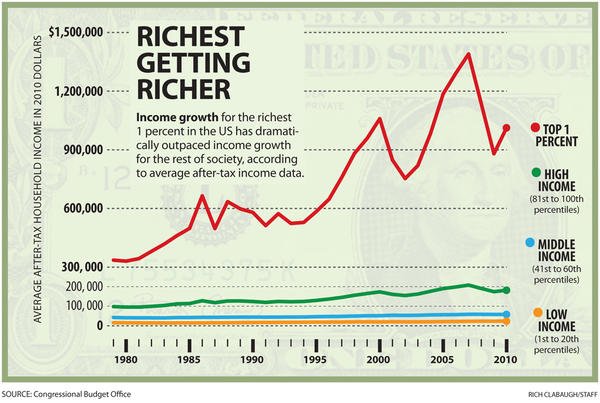

The American middle class must, for our society to be sustainable, represent the bulge of the bell curve. Yet by many measures the bulge is becoming a parabola. And the hyperwealthy represent the tip of a very steep curve.

As Galston notes, the wealthy were hit during the recession, but only the middle class continues to feel its effects:

. . . the now-famous 1 percent was breaking away from the pack. The gap between the compensation of corporate leaders and the wages of their workers increased many times over, and the surge of the financial sector produced a new tranche of packagers, traders, and managers who enjoy almost unimaginable wealth. (The advertisements in the New York Times Sunday Magazine convey some sense of how the new class of super-rich spends this wealth.) All the while, middle class families have been treading water, and many parents fear that their children will do worse.

The Great Recession still troubles the middle class

Although technically the recession (small “r”) ended in June or July of 2009, the Recession still troubles the middle class. One recent Wall Street Journal poll found that 76% of adults lack confidence that their children’s generation will have a better life than they do—an all-time high. Some 71% of adults think the country is on the wrong track. That’s a leap of 8 points from a June survey. And no fewer than 60% of Americans believe the U.S. is in a state of decline. As Galston notes: “Allowing for inflation, median annual earnings of workers with BAs have not increased in the past three decades.”

Galston suggests three specific policy prescriptions: aim for full employment, create tax incentives for businesses to share profits with workers, and stop giving tax cuts to the wealthy. But even these policies may not be enough. Maybe we should break up the big banks.

“There is no reason to expect that . . . the middle class will rebound,” Glaston warns. What he sets to words the middle class has enough sense to know instinctively.